Part 4 of the series I just want what I want! (Thinking about Desires)

Kant and the Principle of Autonomy

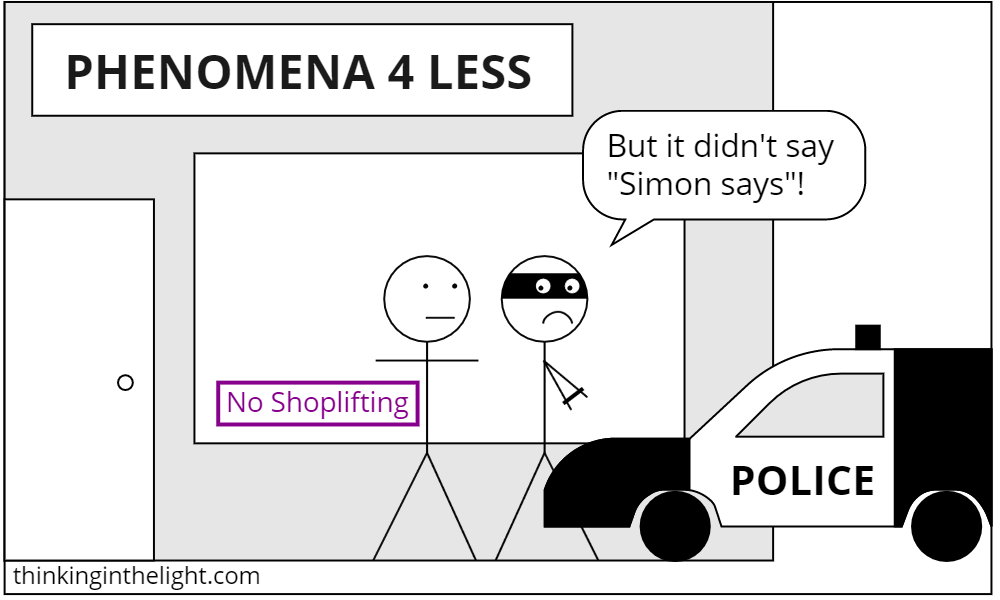

Simon says touch your nose.

Simon says hop on one foot.

Simon says don’t murder your coworker.

We all know why we would do these things in the context of the game, but in real life I don’t go around touching my nose unless I want to. Same with hopping on one foot. So why should I refrain from murdering my hated coworker? (Besides the fact that I might get fired.) Why should I do the right thing if my desires push me to do what is wrong? What motivates me to be moral?

If I want to do the right thing, or if I love the person I am helping and so enjoy helping them, then it is clear why I would do what is right. But as I discussed last time, some argue it is better to separate love and inclination from morality. For this post, therefore, I am thinking about how we might motivate ourselves to be moral if we remove desires from the picture completely.

One possible answer to this question is respect. For example, suppose that I work for a company and have a decent boss. I don’t know her well, so it is not the case that I feel love for her or simply enjoy doing what she asks. But I do respect her. If she asks me to do something I don’t want to do, I will do it because of that respect. “Yes, I will repaint the lunchroom chartreuse.”

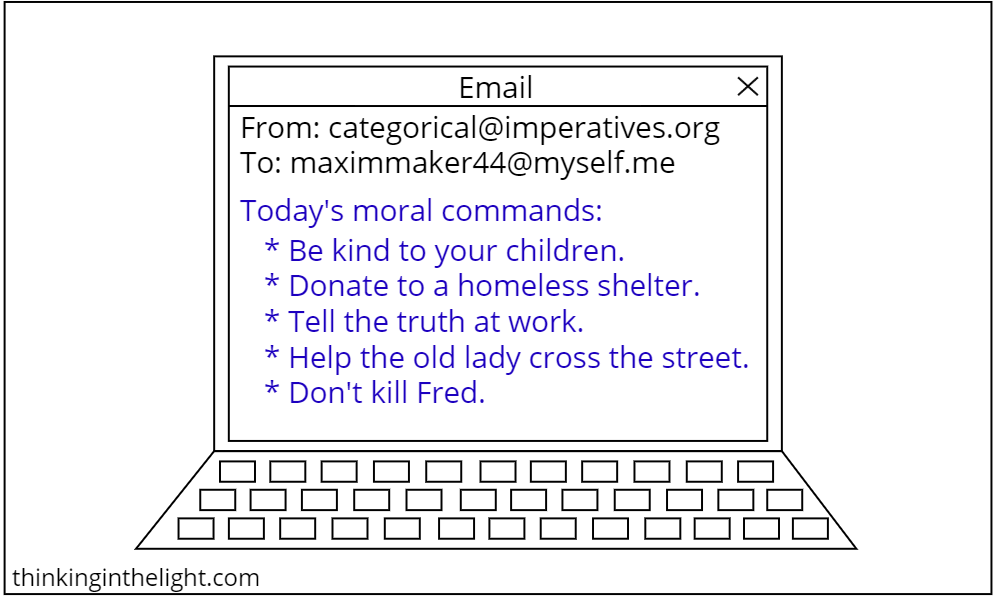

Of course, a respect for morality would have to work a bit differently. First, my boss can ask me to do something immoral. Her decrees are simply hers, not instances of morality. Second, when my boss asks me to do something, the command arrives via email or a knock on the door. But when I am considering whether I should tell the truth that will get me in trouble or lie to keep myself comfortable, no one comes to my door to tell me to do the right thing.

If respect is going to motivate us to act morally, then, we will need an account of this respect. One common account says that what we respect is autonomy. In contemporary discussions this means that to act rightly we must respect the decisions of other people, particularly when these decisions concern themselves. We must allow them to act independently or autonomously. The principle of autonomy is often invoked in medical ethics. Suppose that a doctor is convinced that a patient will live if she undergoes a certain surgery but will die if she does not. However, the patient does not want to undergo the surgery. The principle of autonomy says that the patient should be allowed to decide what will happen to herself, even if her choice results in her death.

This principle of autonomy is quite popular. For example, when someone discusses ethics primarily in terms of consent, they are appealing to the need for autonomy. Consenting means that a person has chosen a certain course of action for themselves and made that choice clear. If the principle of autonomy is the basis of ethics and what we must respect, then consent is all that is needed. Once someone has chosen a course of action, their choice must be respected.

However, though the principle may be popular, it will not serve my needs here. I am seeking a way to motivate morality without appealing to desires, but this principle is all about them. By respecting choices I am respecting desires, since a person typically chooses what they most want. The contemporary principle of autonomy, then, is basically Mill’s harm principle that I already examined, in that the emphasis is on allowing people to make decisions about what affects themselves and doesn’t infringe upon the autonomy of someone else.

This contemporary principle, however, arose in part due to the influence of an earlier principle of autonomy, one put forward by Immanuel Kant. As I discussed last time, Kant does not base morality on desires or love. His account of respect and autonomy is instead grounded in reason. This means it might provide an answer to the question of how to motivate morality without appealing to desires.

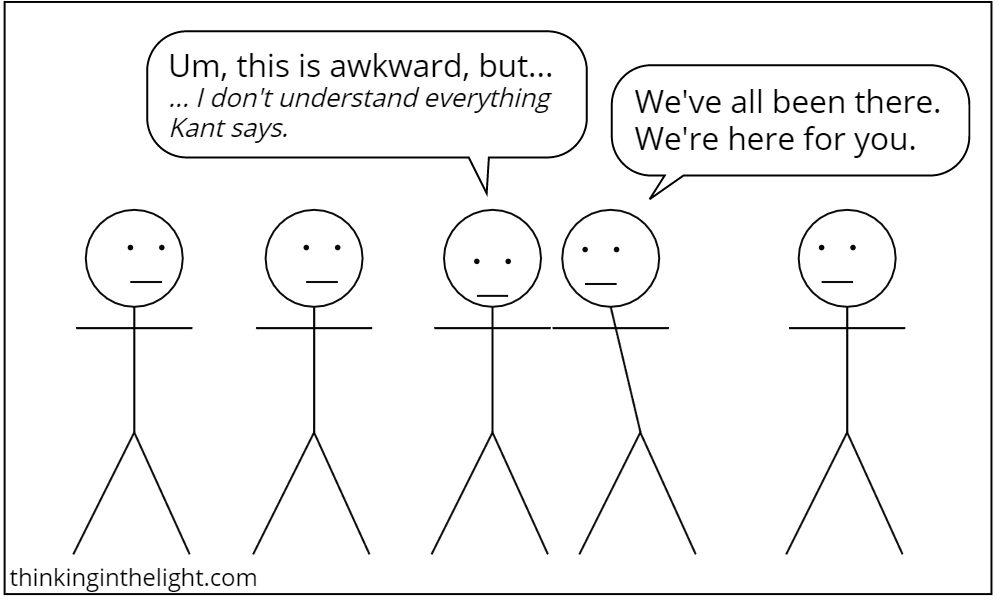

Now, before moving further I feel compelled to issue a caveat. It is not entirely clear that Kant’s account of respect and autonomy is meant to answer this question. This is, in part, because nothing in Kant is entirely clear.

Kant also says at the end of the Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals that it is impossible to explain why morality interests us. It just does. This would mean that we really shouldn’t be looking for a motivation to be moral. However, his emphasis on autonomy is so easily turned into a motivation to be moral that it seems like it might be part of what he is doing. (See previous paragraph regarding Kant and clarity.) So I am going to explore Kant’s account of autonomy as a possible answer to the question I’m thinking about, even if Kant himself would disagree.

That said, Kant explains that I respect morality because I am its autonomous source. I respect the moral law, because I am the one giving it. “Don’t murder!” is not a case of Simon says, but a case of I says. This may sound strange: how is morality coming from me? Before addressing this, however, notice that being the source of the moral law might explain why autonomy would motivate me to be moral.

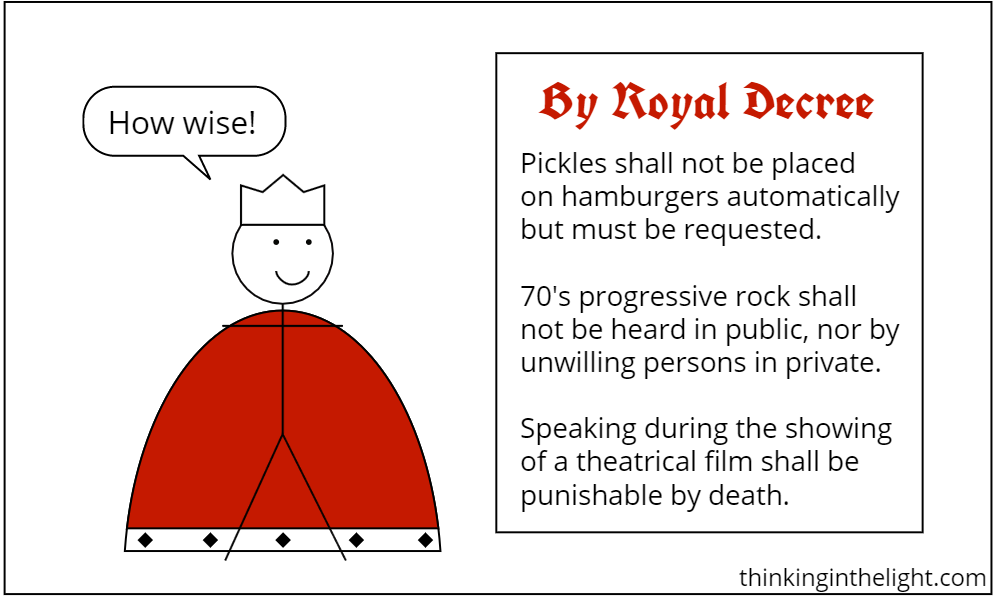

Consider an analogy. We have been talking about the moral law, but think instead about the laws of society. Those laws come from a clear source: the government. Suppose that I live under a harsh dictator. The dictator makes all the laws, and I may follow them out of fear of punishment. I certainly don’t follow them out of respect. If I could get away with ignoring the laws, I would. But now suppose that I am the dictator. When I am following the laws I am simply following what I said to do. I have inherent respect for the source of the legislation, because it was me.

This, of course, gets complicated, since if I am a dictator, my desires may change and I might simply change the laws. Or I might discover that I’m a lousy lawmaker and cease to have respect for myself. Because of this, it is important to note that the moral law is different from the laws of society, especially as Kant conceives the moral law and its relation to autonomy.

When we use the word ‘autonomy’, we usually mean to speak of independence. This is an appropriate use of the term, since it is formed from two Greek words: auto (‘self’) and nomos (‘law’). I give the law to myself rather than receiving it from somewhere else, so I am independent.

In Kant’s usage ‘autonomy’ also means giving the law to myself, but he emphasizes aspects of both self and law that are different from the way we often think. Both of these aspects have to do with the centrality of reason in his thought: we are essentially rational beings and morality flows out of reason. I will do my best in the next few paragraphs to sketch what I understand his position to be. (But see above regarding Kant and clarity.)

To take the second part first, Kant stresses that when we are acting autonomously, we are giving ourselves a law. One of the features of the moral law, according to Kant, is that it is universal. It never changes, and it applies to everyone in every situation. Morality does not depend, then, on what I want, for this changes. Morality does not depend on which people are involved—this also changes—so morality does not depend on the different desires of those different people. The moral law is, therefore, similar to math. In every situation 2 + 2 = 4, no matter what sets of objects it is applied to and no matter who is doing the calculation (assuming they do it correctly).

This means that I am only acting autonomously when I am giving myself rules to act on that are universal—when I am giving myself laws. Morality is not doing what I want, for that is having my actions be dictated by my desires, but morality is giving myself universal laws to act upon.

Autonomy of the will is the property that the will has of being a law to itself (independently of any property of the objects of volition). The principle of autonomy is this: Always choose in such a way that in the same volition the maxims of the choice are at the same time present as universal law.

Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, p. 44

That is, Kant’s principle of autonomy says that the rule I act on (my maxim) must be a rule that everyone always should act on (a universal law). For example, I cannot act on the rule that I will lie to you when it is convenient, because this is not a rule that everyone can always act out of. If everyone always lied when they found it convenient, then lies would never work. Everyone would know that people regularly lie, and so they would never believe what people say. The only way for my lie to work is if my rule is “I will lie when it is convenient,” but the rule everyone else acts on is “I will always tell the truth.” In this case, however, the rule I am giving myself is not universal, since it only applies to me. Therefore, it is not a moral law, so I am not acting autonomously.

And if this does not sound autonomous, because it doesn’t sound like myself is giving the law to me, it is also important to note that Kant has a particular view of the self. According to him, what I am at my core is a rational being. This means that the dictates of reason are more intrinsically a part of myself than anything else. It is true that I have desires, emotions, and so on, but these are in some sense external to me. I am not fully myself when dragged around by these factors, but I am myself when acting rationally. So when my reason is determining universal laws, this means that I am giving myself the laws.

When we are acting autonomously, then, we are acting out of reason, giving ourselves universal laws to follow. It is this fact that generates respect.

Our own will, insofar as it were to act only under the condition of its being able to legislate universal law by means of its maxims—this will, ideally possible for us, is the proper object of respect.

Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, p. 44

OK. Take a deep breath. The dive into Kant is complete and it is time to resurface and summarize. The problem was figuring out what motivates me to do the right thing if I am not using my desires to achieve that motivation. Kant suggests that we can be motivated to respect the moral law because in following it we are acting autonomously—being fully rational and giving ourselves a law that applies to everyone in every situation.

While this position is difficult to understand, I wanted to look at it because appealing to reason is an interesting way to address the problem. No one asks why they should care about and follow the basic rules of math. We simply see that deciding I want 2 + 2 to equal 5 is irrational. So if morality is shown to be similar to math, then we have a similar motivation to be moral.

However, this sketch of Kant’s principle of autonomy also highlights at least two problems with basing morality completely in reason. First, he says that we are primarily rational, but our desires and emotions seem to be at least as much a part of us as our reason. All of these facets of myself give me information about the world, and all of them can lead me astray if I let them. Reason can stop my desires and emotions from pulling me in a direction I know is wrong, but it can also be used to rationalize my behavior. Emotions can lead me to do things I regret, but they can also prompt me to do the right thing that is objectively inconvenient. Reason is important, but it does not exhaust who I am. We all need both Spock and Kirk aboard our mental Enterprises.

Second, Kant also says that moral laws are universal, but there is good reason to think he is too strict. He famously argues that it is always wrong to lie. It is even wrong to lie to someone who is trying to murder your friend and asks where he is. However, while 2 + 2 may always be 4, it seems better to say that it is just usually wrong to lie. Morality is a lot more nuanced than mathematics, so rather than consisting of strict universal rules, morality needs to take into account the particular situations involved.

There is a lot more that could be said, but you don’t want to read a book about Kant and I don’t want to write one. My purposes for this post have been achieved. In order to think more about desires and morality, I wanted to introduce a few ideas: 1) If we are not motivated to be moral by desires, perhaps we could instead be motivated by respect. 2) Explaining this respect by solely appealing to reason is an interesting but problematic strategy. 3) Explaining this respect by appealing to the contemporary principle of autonomy simply falls back to having morality be based in desires.

This post has ended up more complicated than I envisioned it being. (Thanks, Kant!) But it does illustrate that it is difficult to motivate morality without appealing to desires at all. Perhaps, then, what is needed is a mid-way account, one that avoids saying desires are everything while at the same time not saying that they are nothing. Perhaps some desires can be used as a way to motivate us to forsake others. This is what I will examine in the next post—one which will be much less complicated, because it will not be about Kant.

Bibliography:

- Immanuel Kant. Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals. [1785.] Translated by James W. Ellington. Third edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1993. (If you want to look at what Kant says, the material about respect comes in the first section of the Grounding, while the discussion of autonomy is at the end of the second. He discusses never lying in On a Supposed Right to Lie Because of Philanthropic Concerns, which is included in the Hackett edition above. Kant is quite difficult to read, however, and I admit that what I have explained above in the post is an attempt to make what he says understandable, an attempt not always based solely on what Kant says. My explanation in part reflects the argument that Kant’s account of autonomy is drawing on elements of Rousseau’s theory of the general will in On the Social Contract. (See, for example this.) So there may be bits of Rousseau creeping in that don’t belong.)