Part 6 of the series I just want what I want! (Thinking about Desires)

Moral Motivation in the Bible

You only live once.

As a factual statement, this is hard to dispute. All around us we see people being born, living, then dying and not coming back. (If you are reading this after the zombie apocalypse, I guess that last part turned out to be false. Sorry.) When it comes to life on this planet, we clearly get one shot. You do only live once.

When we say this, however, we are not just stating a fact. We mean it to be inspirational. You only live once, so follow your dream. Do the thing that you want to do but scares you. Eat that piece of cake, or maybe even two. That is, we assume we know what follows logically from the fact. You have one shot at life, so act on your desires.

However, if you only live once, isn’t it also true that you only have one chance to be a good person? I have one shot to live a life where I do the right thing. This is also an implication of my single lifetime. Which implication we acknowledge depends upon whether we find it more important to follow our desires or to be moral.

In this series I have been looking at the relationship between desires and morality, and in this last post I want to revisit a few of the ideas I find most compelling.

First, it makes most sense to say that some desires are wrong, that doing the right thing is something different than trying to satisfy as many desires as possible. Each of us wants many things, and only some of them are things we should have.

If this is the case, and I at times have to act against my desires, then the question arises as to why I should do so. What motivates me to abandon desires and act morally? I have looked at several answers to this question in the preceding posts, and three things stand out.

- Kant indicated some problems with having love be my motive, but what if I was motivated by love for everyone?

- It is an interesting idea to propose respect as the motivation, even though Kant’s version of this proposal is not the way to go.

- It is also worth considering that we might be motivated by a vision of our ideal self, as long as this ideal is not self-generated.

There is much more that could be said about desires and the motivation to be moral. Philosophers have been writing about them for centuries, so clearly I have not covered every conceivable aspect of their relationship.

What I want to do now, though, is to look at some of what the Bible has to say about desires and morality. In particular, it provides a picture of how all the points I highlight above could be unified.

To begin, the Bible is clear that not all desires are good. In the story of Adam and Eve, God gave them a garden full of fruit and told them that they could eat any of it, besides the fruit of one tree—the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. One day the serpent came to Eve and proposed that God was withholding something good by forbidding the fruit of this tree. The proposal piqued her interest.

So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate…

Genesis 3:6

God said “No,” but Eve’s desires said “Yes,” and she went with the desires.

This is pretty much the prototypical bad desire—knowing something is wrong but wanting to do it anyway—but it is also pretty easy to identify with. We all experience these desires. (I mean, it’s not just me… right?) The fact that the Bible portrays so many recognizably flawed characters is one of its strengths. It realistically shows the way that humans often prioritize their desires over what they should do, and like some of the philosophers I have looked at in this series, it sees this prioritization as a problem.

So, given that we all want in ways we shouldn’t, what motivates us to do what we should? Often, when the motivation to be moral is discussed in a religious context, it is assumed that the motivator is fear—fear of punishment. I do the right thing because I fear going to hell. Now, the Bible does speak in these terms at times.

And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell.

Matthew 10:28

I naturally fear the human beings who can end my mortal life, but Jesus is recommending that I fear God instead, since he can do worse.

However, often when the Bible advises that we fear God, the term “fear” means something closer to respect. For example, the book of Proverbs is about finding wisdom, and the root of wisdom is identified as fearing God.

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight.

Proverbs 9:10

This fear has an element of remembering that God can bring consequences upon me if I stray off the path he has laid. But more importantly, it is pointing to the fact that the path is there in the first place and was laid by the one who created the universe. God knows more about everything than I do, so if I will conform my life to his instructions, I will benefit from doing so.

Trust in the Lord with all your heart,

Proverbs 3:5-8

and do not lean on your own understanding.

In all your ways acknowledge him,

and he will make straight your paths.

Be not wise in your own eyes;

fear the Lord, and turn away from evil.

It will be healing to your flesh

and refreshment to your bones.

When I fear God I am respecting who he is, and I am acknowledging the fact that I am not God. This sort of respect seems like an appropriate motivator for my actions. For respect to motivate, it must be grounded in something. Kant tried to ground it in autonomy—the fact that I am giving rules to myself—but this runs into problems. A better ground is recognizing that the source of the rules is a good and appropriate source, and in particular that it is a better source than I would be. I desire certain things, and these things may run counter to what God says I should do. But in respecting God I am acknowledging that he knows better, so if I am rational I will follow what he advises rather than what my desires dictate.

In addition to fear, the Bible also speaks of morality in terms of love. For example, Jesus focuses on love when summarizing our moral obligations.

“Teacher, which is the great commandment in the law?” And [Jesus] said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

Matthew 22:36-40

This love can also serve as a motivation for me to do the right thing, rather than acting on my desires. I won’t say anything here about loving God, since this is closely tied to the fear and respect just discussed. But when it comes to loving my neighbor the issues I examined in a previous post immediately arise: love is closely tied to desire, so if I do good to those whom I love, this can often lead to me ignoring those whom I don’t.

On the one hand, this is not a problem for the love Jesus commands. He makes it clear (in stories like the one about the good Samaritan) that our “neighbors” are ultimately everyone we come across. We don’t get to pick out those for whom we currently feel love and help them. We are to love everyone.

On the other hand, even if I am loving everyone, is it still a problem if I am serving people based on this love, and this love is a reflection of my desires or inclinations? Kant thinks so. He thinks that this command of Jesus must be referring to a different kind of love.

For love as an inclination cannot be commanded; but beneficence from duty, when no inclination impels us and even when a natural and unconquerable aversion opposes such beneficence, is practical, and not pathological, love. Such love resides in the will and not in the propensities of feeling, in principles of action and not in tender sympathy; and only this practical love can be commanded.

Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, p. 12

This explanation can sound good: how could we possibly be told to feel sympathetic to someone to whom we are indifferent, or even to someone we dislike? But love divorced from desire and feeling is not what Jesus is talking about. He tells me to love my neighbor as myself. I don’t just rationally choose to provide for my needs, but I am passionately committed to ensuring my own welfare.

If I am to love another person as myself, it will have to involve feeling, sympathy, and desire, because these are all essential components of my self-love. I could object that achieving this sort of love for someone else is very difficult or even impossible, but this doesn’t mean that the standard is faulty or needs to be lowered. The problem is with me and my lack of love. The sort of person Jesus commands me to be is the sort of person I should be, even if I am unable to get myself there. If I can’t fully reach that point myself, then rather than eliminate or lower the standard, I could instead admit that I need help reaching it. To be this sort of person, I need God to change me.

The radical nature of this love also solves the problem of making love the foundation of morality, as raised above. When we think of love, we think of the flimsy sort that we regularly experience. It is inconstant and fluctuates with my changing momentary desires, because it is focused on me. This sort of love is no basis for morality. It is simply an expression of my desires, including the problematic ones. But the sort of love that Jesus asks us to have is different. This love also desires, but it desires for everyone to do well, and it does so consistently. If someone had a love like this and lived out of it, they would not be favoring some over others, nor would they be changing their mind later and so be changing their actions. A person with this sort of love would be the ideal moral agent.

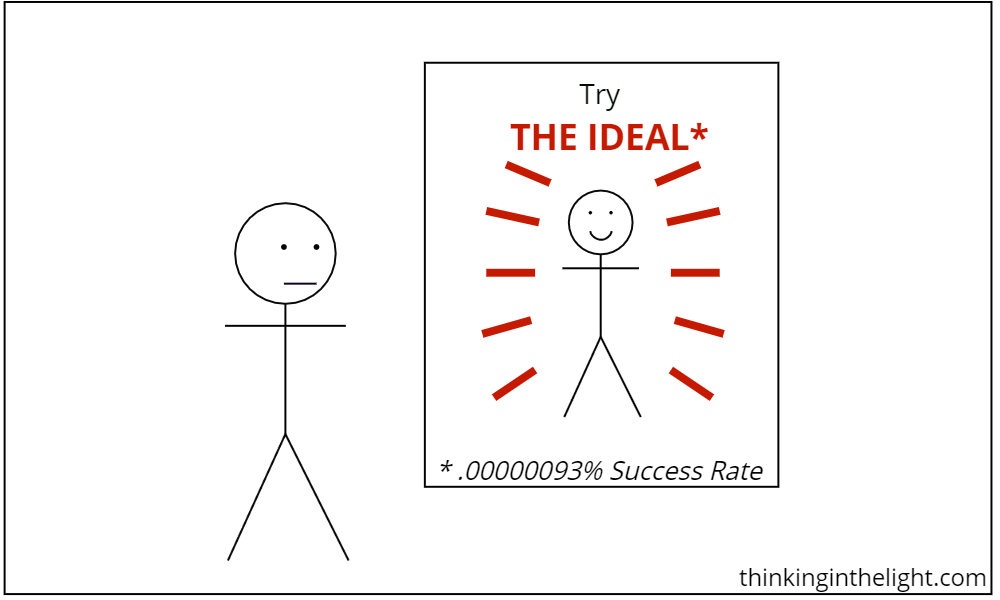

While the Bible upholds this vision of love, it also is realistic about the fact that most people don’t achieve this ideal. In fact, it says that only one person has ever been this loving: Jesus. Looking at this statistic, I might be discouraged from adopting this ideal as the one I strive for in my own life.

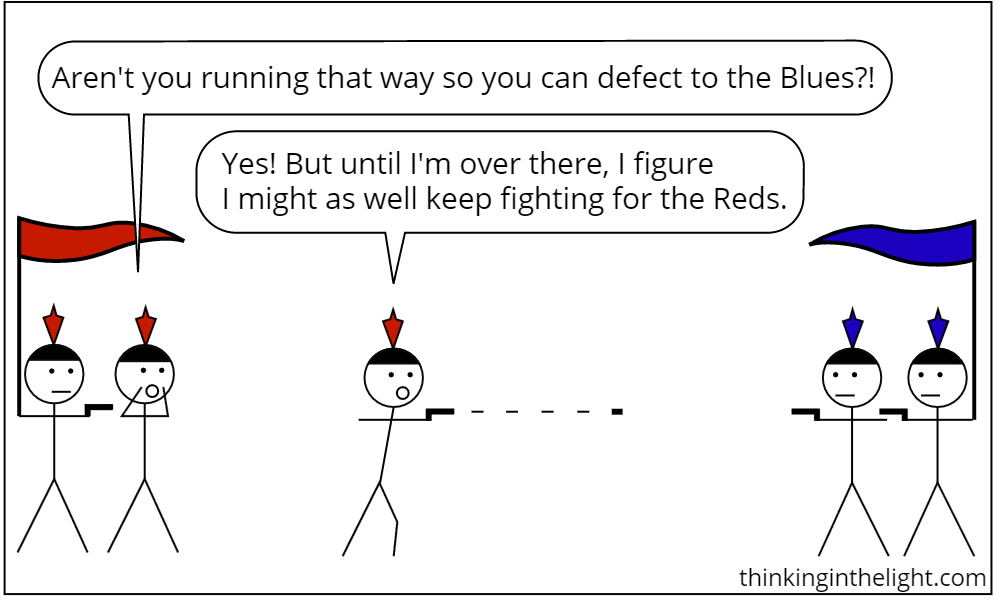

But the Bible holds that this ideal should motivate me. This is because it is not merely some abstract ideal out there, but through God’s work it is actually my ideal self as well. We are all naturally in the state where we act on our desires and ignore God. This puts us at enmity with God and deserving of his anger. (Kind of like how if I decide at work to ignore my boss and just do what I want, I can expect to be fired.) God, however, reaches out with an offer of forgiveness and restoration through Jesus. In the ultimate reversal, Jesus took on the punishment that was ours and offers us the status that is his. All that we have to do is accept the offer. In Ephesians it describes this state that the Christian has been rescued from, and how God rescued me due to his love and not based on anything I did.

And you were dead in the trespasses and sins in which you once walked… [living] in the passions of [your] flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved—and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, so that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness towards us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast.

Ephesians 2:1-9

As a result of being rescued there are now two things that are true of a Christian. First, I have been identified with Jesus. It says here that Christians are made alive together with Christ and raised up with him in the heavenly places, and this language is used because his status has been applied to them. (I don’t know about you, but I have neither been literally resurrected nor recently taken a trip to heaven.) Second, the destiny of the Christian is to be in God’s kingdom in the coming ages—that is, after life on this earth. The Bible makes clear elsewhere that one of the qualities of God’s kingdom is that all its residents will shed their moral imperfection. I will love perfectly like I am unable to now.

Because of my identification with Jesus and my future status as a moral person, the Bible points out that this affects the way I think about my behavior now. I shouldn’t just continue to do whatever I want, but I should instead strive to live like Jesus. Ephesians puts this in terms of living like my old self or my new self.

Now this I say and testify in the Lord, that you must no longer walk as [those who are not following God]… [Instead you ought] to put off your old self, which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful desires, and to be renewed in the spirit of your minds, and to put on the new self, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness.

Ephesians 4:17, 22-24

By using this language of “the new self,” the Bible is making it clear that the perfectly-loving ideal moral agent described before is not merely an abstract, unreachable ideal. It is a vision of my ideal self. I may not be able to achieve it now, but because of the promises of God, I have 100% certainty of achieving it one day. Thus, as my destination, it makes sense that it guides my vision now. It is an ideal self that is actually motivating.

When it comes to desires and morality, the Bible includes worthwhile elements from all the positions I have looked at in this series. It recognizes that our desires are often for the wrong things. It explains morality in terms of love. It motivates us to choose morality over our desires both by appealing to respect for God (an appropriate object of respect) and a picture of our ideal self (an ideal we will one day reach).

I suspect that the biggest objection to the position outlined here is to wonder how I know that the Bible is true. This is a big question to answer, but I would say in response that all our beliefs are ultimately held based on their coherence—on how good a job they do at fitting together to form a picture of the world that works. And I would argue that the Bible is at least as good at explaining morality and its relation to our desires as the other philosophical systems I have examined. Actually, I have just argued that it is better. If that is the case, then this is not proof that it is telling the truth—but it is evidence. As I sketch out in Why Christianity?, if the Bible puts forward a more coherent picture of my experience than other available accounts of the world, then its claims to have the truth should be taken seriously.

I have now reached the end of this series. There is so much more that could be said about desires. (In fact, I already have another series planned for the future!) I hope that thinking about desires and morality has been helpful to you the way that it has been to me.

This is the first series I have done for Thinking in the Light, and it is a project I have been planning for a long time, so I am excited to have actually brought it into existence. And I am also excited to get started on the next series I have planned (and then the one after that)! I know that wanting to write posts about philosophy and illustrate them with stick figures is probably not the world’s most popular hobby. But what can I say? I just want what I want.

Bibliography:

- The Holy Bible, English Standard Version® (ESV®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. (If you want to look more at what the Bible says about fearing God, the book of Proverbs is a key book to read. The first nine chapters, in particular, tie together the ideas of God being the creator, him wanting us to live a moral life, and the way we benefit from so living. When it comes to the idea of the new self, looking at the context in the book of Ephesians is worthwhile. My own thinking has been influenced by the discussion of identity in Clinton E. Arnold, Ephesians, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament, 2010.)

- Immanuel Kant. Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals. [1785.] Translated by James W. Ellington. Third edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1993.