Part 3 of the series I just want what I want! (Thinking about Desires)

Kant and the Good Will

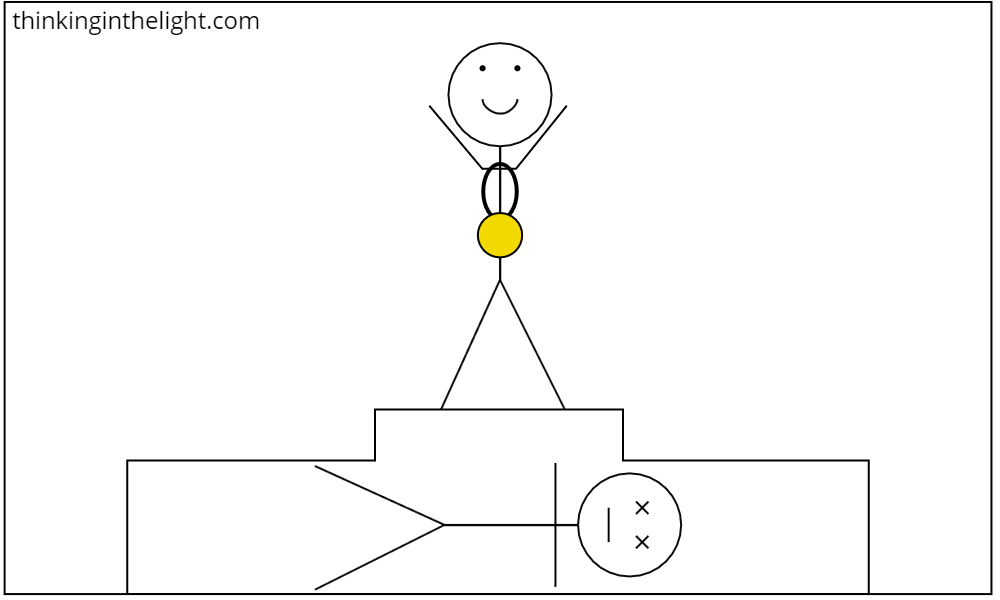

Ever since she was a little girl, Danielle has had a dream. Achieving it is the goal she has been working towards her entire life. And today she has accomplished it.

She is overcome with happiness. Her greatest desire—practically her only desire—has been to reach this point, and now the desire has been satisfied. This desire has helped her get through the tough times, and finally reaching the goal lets her look back over her life and know that it was all worth it. Inside, she is experiencing pure euphoria. Because she did it! She finally murdered someone.

Many people would not like the fact that Danielle gets to experience this happiness, and Immanuel Kant would be one of them. Kant was a German philosopher writing in the late 1700s, and in contrast to John Stuart Mill, Kant does not think that happiness is always good. Even before my desire conflicts with that of someone else, it is not always good to satisfy it. That is, happiness is not good in itself. It is not good without qualification. Certain conditions have to be met before happiness is good, because the only thing that is always good is a good will:

There is no possibility of thinking of anything at all in the world, or even out of it, which can be regarded as good without qualification, except a good will.

Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, p. 7

By “good will” Kant does not mean wishing someone well or spreading cheer at Christmas. A person has a good will when they choose to do an action because it is the right thing to do. A good will is what the moral person has.

Kant thinks we all recognize that being moral is better than being happy, that we prefer a person who does what is right to one who is happy from doing what they want. He makes this point in two ways.

First, we can think about what other traits the happy person and the moral person might develop. For example, if I am happy—if I am doing well and am contented—then I might look around at others who are not happy and feel a bit better than them. I might even think that I deserve this happiness because I am intrinsically superior. This means that happiness can actually lead to the bad quality of arrogance.

By contrast, if I am acting out of a good will, if I am doing the right thing because it is the right thing, then I won’t develop this bad trait. I am trying to do the right thing, and avoiding arrogance would be part of my goal. Of course, it is important that I’m doing it because it is the right thing and not because I want to be seen as someone who does the right thing. The self-righteous person is clearly not immune to arrogance.

Second, Kant also prefers the moral person to the happy one when considering each quality solely in relation to the other. Imagine two people. One is completely happy but also immoral. They cheated, lied, and backstabbed to achieve their contentment. The other is not happy, but they always do what is right because it is right. Despite their lack of happiness, they continue to do the right thing.

Kant thinks that everyone will recognize a problem with the first person.

The sight of a being who is not graced by any touch of a pure and good will but who yet enjoys an uninterrupted prosperity can never delight a rational and impartial spectator. Thus a good will seems to constitute the indispensable condition of being even worthy of happiness.

Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, p. 7

That is, we think that the first person does not deserve to be happy, while the second does. If I tell you that Hitler was very happy for the last month of his life, your reaction is most likely not to say, “Oh, that’s nice.” And if I tell you about Katie, a single mom who works two jobs to support her kids and who still finds time to serve the homeless population in her city, and I tell you that she does not feel happy, because she does not feel supported by anyone else, then you will likely wish that this situation could be remedied. Given her service to others, it seems only right that she would get happiness.

Kant’s examples here may not convince someone who is committed to the idea that morality is irrelevant and fulfilling our desires is everything. But if you are sympathetic to the idea that doing the right thing takes precedence over doing what I want, then these are nice clarifications of that idea. Doing right is superior to being happy, since only doing right is always right. Satisfying my desires is not good in itself, but it is only good when those desires are moral. As Kant goes on, he makes an even clearer contrast between desires and morality, although the new material raises some potential questions as well.

This contrast comes out in Kant’s discussion of motives. In his view, it is not enough to do the right thing, but it matters why we do it. That is, the motive matters. If I do the right thing simply because I want to, then the action does not display a good will and does not have moral worth. On the other hand, if I do the right thing because it is the right thing, then I have a good will and the action does have moral worth. In the first case I am acting out of desire, in the second I am acting out of duty.

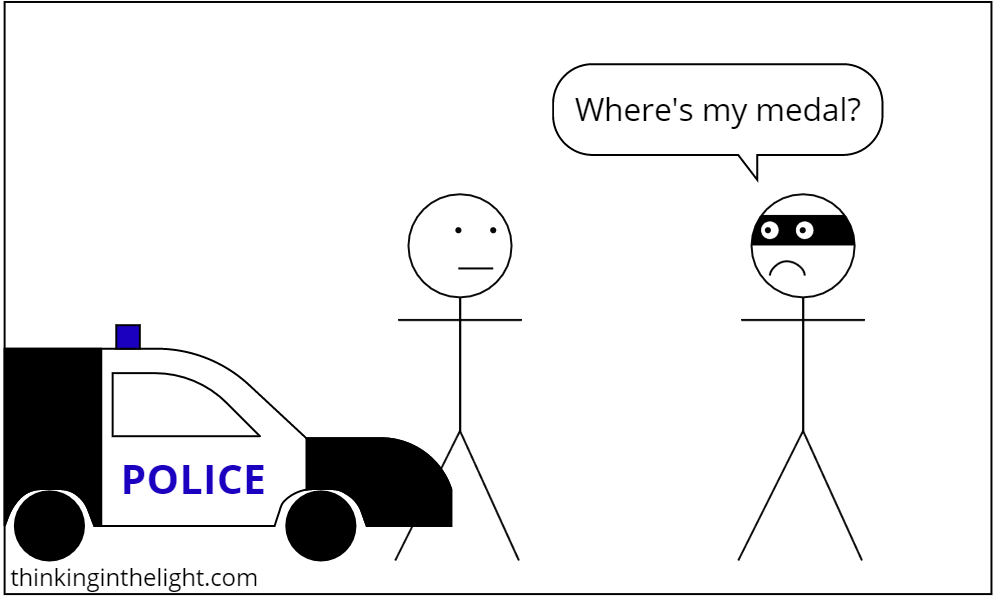

Moral worth, then, is something different from being right. For example, suppose that Martin is about to rob a house, but as he is walking up, a police car goes by. He suppresses his desire to steal and leaves the area instead. Martin did the right thing—he did not commit a robbery—but few people would think he should be praised for his action. He was acting out of self-interest, not displaying moral virtue.

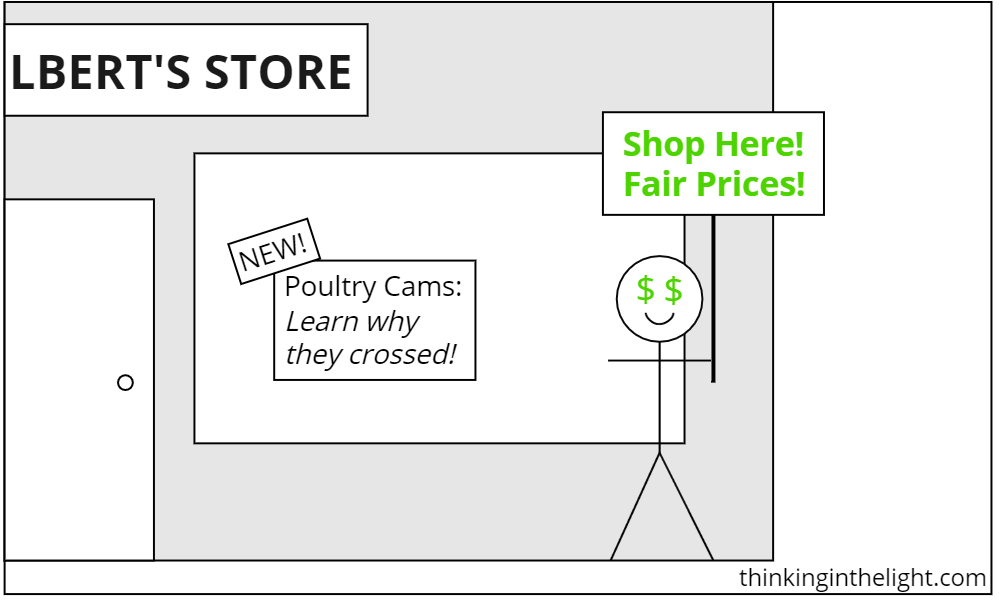

Kant gives a nice example to illustrate the different sorts of motives we may have. Consider a store owner. It is wrong for an owner to take advantage of their customers by charging extra when they think they can get away with it, such as when children or people with visual impairments are shopping. The right thing to do is to charge the same fair price, no matter who is buying. But even when an owner sets consistent prices and does the right thing, there are different reasons they may do so.

Owner A keeps his prices consistent because he realizes that this is in his long-term interest. If people hear that he has shady business practices they will not shop at his store. Therefore, he charges people fairly—he does the right thing—because he desires to. Not that he desires to do so because it is the right thing, or even because he wants to charge fairly. He simply desires money, and this course of action is the means to achieve his desire.

Owner B keeps her prices consistent as well, and she also does so based on her desires. It is not money that she wants, however, but she loves her customers so much that she enjoys helping them and wants to charge them fairly. She differs from owner A in that his desires were focused on his long-term interests, whereas B’s desire is simply to charge people the same amounts. In Kant’s terminology, she has an immediate inclination towards doing the right action. But Kant would still say that her action does not have moral worth. It is not morally praiseworthy.

Both A and B were doing the right thing because this action aligned with their desires. Owner C, on the other hand, charges honestly because it is the right thing to do. She may want to or may not want to, but in either case her desires are irrelevant because she is moved by duty. For Kant, even though all three owners are doing the same thing, only C is displaying a good will and acting in a way that should be praised as moral.

Now, it could be that when it comes to a given action I both want to do it and also do it because it is my duty. But it is just as likely—or maybe even more likely—that I simply do what I want, without caring what my duty may be. By separating the different motives, Kant highlights this potential conflict between my desires and the right thing to do. For example, what would happen if the desires of the three shop owners changed? If A stopped caring about money or B stopped caring about people, then both of them would change their action and might no longer do the right thing. Their desires would no longer align with morality. But C’s actions would not change, because her motive was not based on her desires.

What Kant says here makes quire a bit of sense, although there are significant reasons we could disagree with him. I will set aside those that question the need to examine motives at all. (The case of owner A is an instance of the invisible hand of economics at work, with self-interest leading to the good of the whole society, so does it really matter why he charges fair prices?) Instead, we might agree that our motive is a fundamental part of morality, but we might still wonder about Kant’s treatment of owner B. Isn’t loving someone a good reason to act—even a better reason than an abstract “I must do the right thing”?

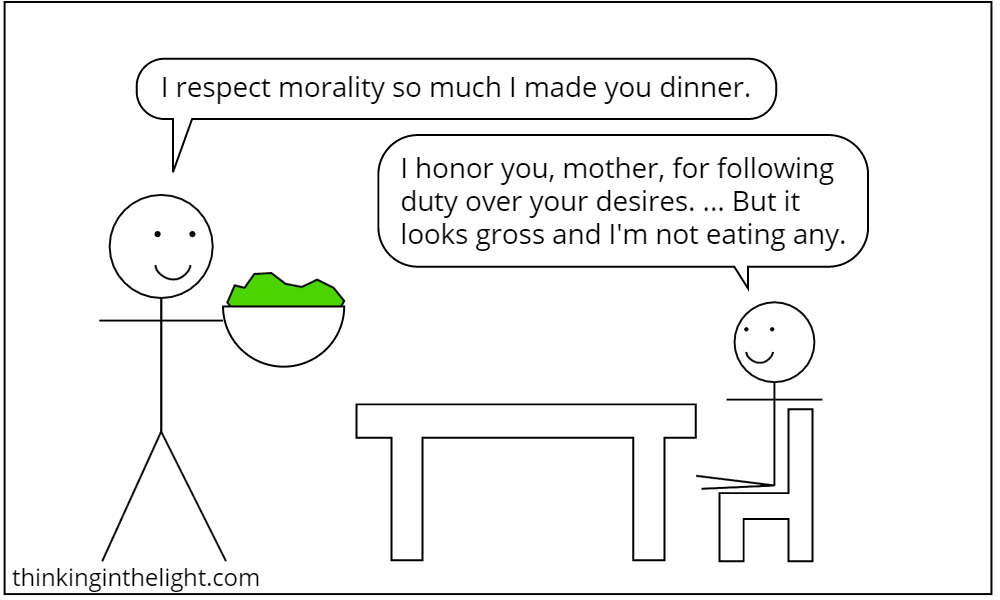

Suppose that Katie’s children are well-fed, and one day they decide to thank her for all her work preparing food. (I know this is a far-fetched example.) “Thank you,” they say, “for showing your love to us by making us meals.” Katie responds, “Oh, I don’t feed you because I love you. I feed you because I recognize it is my duty.” Katie’s response sounds cold, so cold that it sounds wrong. By contrast, a mother who serves her children out of love might even be seen as a supreme example of moral behavior.

In Kant’s defense, he is right about a mother who is feeding her children simply because she enjoys doing so. When she no longer enjoys it, she might stop feeding them. She is merely acting upon her desires in a socially beneficial way. It is also the case that acting out of love can lead to immoral situations. If a mother loves her children, and so feeds them, but there are other children she ignores because she does not love them, this can be very wrong. (Think of Cinderella’s stepmother.)

However, suppose that a person actually had love for everyone, and so they wanted to do good to everyone. This seems like a very moral person, perhaps even more moral than the person who is merely committed to duty. This is an objection worth examining more, and I will bring it up again in a later post. Kant disagrees with it, however, and I am going to examine his position more closely in the next post before returning to the objection.

But before moving forwards, let me look backwards to the previous post and compare Kant to Mill, since the two thinkers take very different positions. Kant sees a tension between duty and desires, which means that he is not concerned about the conflicts in desires that arise between members of the same society. The goal is not to make sure that everyone gets as many of their desires satisfied as possible. Instead, everyone should be focused on simply doing what is right. We shouldn’t be maximizing the satisfaction of desires. We should be shifting our motives away from them.

For example, one way to address an issue like prostitution would be to consult people’s wishes regarding it. Some people want to be prostitutes, some want to visit them, while others don’t want prostitution to be going on in their society. We might also bring in an evaluation of the harms and benefits produced by prostitution and how these affect people’s other desires. All these various desires conflict, so we would try to maximize the desires satisfied. Kant would instead ask, “Is prostitution moral?” It is irrelevant who desires it and who doesn’t. It is irrelevant what sort of harm or benefits result. The only question is whether it is right or wrong. Even if everyone approved and benefited from it, if it is immoral, no one should take part in it.

In the next post I will continue to examine Kant, and in particular I will address two questions that arise from what I’ve discussed here. First, since desires can conflict with morality, one can ask where the morality comes from. I know what it is to want something, and I know what it is to have my desires overruled by those of others. But what makes an action simply wrong, regardless of my desires? This is an important question, but it is a huge one. In this series of posts I am not able to focus on it, but it will be necessary to look a bit at Kant’s answer next time.

Second, given that my desires can conflict with morality, why should I ignore my desires and be moral instead? If someone told me that I should not do what I want, but I should follow everything Kylie says to do, I would naturally be skeptical. Why should my choices be dictated by Kylie? So, similarly, why should my choices be dictated by morality, rather than by my desires?

This second question will be the focus of the next two posts, as I examine differing ways to motivate morality in the face of conflicting desires.

Bibliography:

- Immanuel Kant. Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals. [1785.] Translated by James W. Ellington. Third edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1993. (I do not recommend reading Kant unless you are really invested in studying philosophy—or are assigned it in a class. He is incredibly difficult to follow, especially without help or background. But, if you insist, the discussion of the good will and of the different motives is found in the first section of the Grounding. I do recommend the Hackett edition above, since it has several helpful footnotes from the editor.)