Epicurus on Death Without Fear

Part 1 of the series Shuffled Off (Thinking about Death)

You and I share something in common. (Besides the fact that we have both read these words.) You, I, everyone you know and everyone you don’t—all of us are inevitably going to die.

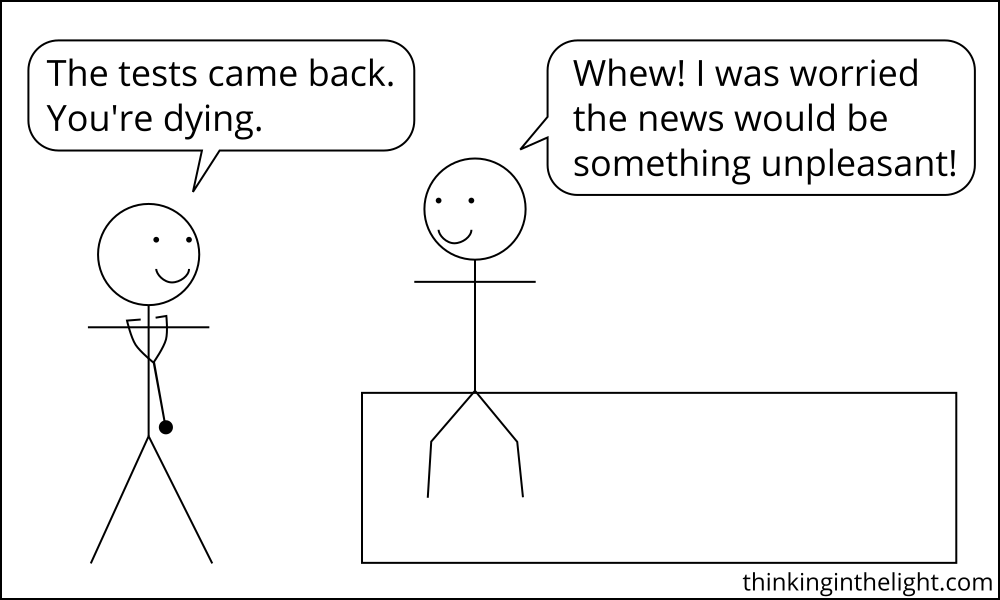

But let’s turn it around and look on the bright side. I know something else about you as well, something I can infer from the fact that you are currently reading this. You are not dead yet.

These two statements summarize a key aspect of being human in this world. We are alive now, but one day we will die. Death is the dark gate standing at the end of our earthly stories, casting its long shadow over the entirety of our lives.

(So, it looks like depressing thoughts will run rampant in this post. As an antidote, perhaps you can simply remember your favorite things—raindrops on roses, whiskers on kittens, and so on. Then you won’t feel so bad. … Just don’t remember that the roses and kittens, too, will all surely die.)

Death is a given in this world, and as humans on earth we are all in the state of being pre-dead. This means every one of us has a question to address: I will die, and the people around me will die, so how should I think about the inevitable fact of death?

Everyone knows that this question applies to them, but many people either refuse to consider it or in practice simply don’t. Even when addressing the question it is easy to let it be academic. As someone who teaches philosophy, I’m pretty much professionally obligated to address big questions like this, but I have often taught philosophies of death without thinking about how they affect me. That is, not really thinking about it.

This series on death, however, is different. It is different, because in January my dad died. I have known grandparents who died, heard of celebrity deaths and the deaths of people my own age. But I was particularly close to my dad, and his passing was the first time that death touched me deeply. In these posts, therefore, I want to examine the various philosophies not just from an intellectual angle, but from a visceral one as well.

But before I get to any philosophers, I am going to begin with Hamlet. Even if you have never read or watched a play by Shakespeare, you are likely to have heard the opening to one of the most famous speeches in the English language: “To be, or not to be.” This speech, if you were not aware, is a poetic rumination on suicide.

Hamlet is considering whether killing oneself would be a good way to avoid the pain that comes with living.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Hamlet, Act III, Scene I

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?

He is wondering whether he should let bad fortune rule him, or whether he should fight back by exiting this world. Is it better to live (to be) or not to live? It looks like the latter might be preferable.

However, Hamlet soon comes to a problem with making suicide the solution: he doesn’t know what lies on the other side of death, and it might be even worse than the things in life he is fleeing.

To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause.

If death is analogous to sleep, then what if there is also an analogy to dreams? What if the experience of being dead is horrible? Maybe it is being tortured forever for living the wrong way. Maybe it is existing in darkness and longing for the light of the living. Maybe it is eternity in a cafeteria with lukewarm french fries and an empty ketchup dispenser. When we have died—or in that wonderfully poetic euphemism, “shuffled off this mortal coil”—we don’t know what we will find.

It is at this point that philosophy swoops in to save the day. Or at least the philosopher Epicurus tries to.

Epicurus is an ancient Greek philosopher who wants to help people live the best life possible. A central concern of his philosophy is to address Hamlet’s worry about what happens after death. And even though he wrote a long time ago, the position he takes is still very popular. He says that in death there is nothing to fear, because death is nothing. Death is not something bad.

In contrast to Hamlet’s concern about an afterlife, Epicurus is confident that death is simply nonexistence. In fact, he would say he knows that death is like this. He knows this because he is committed to empirical science, and in his view this science shows clearly that experience after death is impossible.

Epicurus begins his account of death by arguing that everything in existence is made up of matter. There is nothing immaterial. Specifically, everything is an arrangement of atoms surrounded by space, or void.

Further, the whole of being consists of bodies and space. For the existence of bodies is everywhere attested by sense itself, and it is upon sensation that reason must rely when it attempts to infer the unknown from the known. And if there were no space (which we call also void and place and intangible nature), bodies would have nothing in which to be and through which to move, as they are plainly seen to move. Beyond bodies and space there is nothing which by mental apprehension or on its analogy we can conceive to exist.

Epicurus, Letter to Herodotus (D.L. 10.39-40)

Epicurus, then, is committed to materialism, because his senses are the only tool he trusts to give him knowledge, and his senses show him nothing but matter.

And if everything in existence is made of atoms, this also includes the soul. Epicurus thinks of the soul as particularly fine atoms that enter into a body and make it animated. (You can sort of picture magical sand that is poured into a body and distributed all throughout it.) This account of soul atoms may sound ridiculous, but if we tweak it a bit by updating the science, his general picture is one that many people endorse. Rather than having the soul be little atoms bouncing around, have it instead be electrical impulses in the brain. This is still materialistic, the way Epicurus wants, but it fits better with what we now know about the workings of the body.

For Epicurus, it is important to understand soul, because soul is what makes the body alive, makes it animated. When a body has soul it can move and perceive, and when it doesn’t it can’t. Importantly, Epicurus emphasizes that for perception to happen there must be a combination of soul and body. A soulless body has the equipment but it doesn’t do anything, while a bodyless soul is like power with nothing to make go. In the modern version, a body without any electrical impulses is not alive and can’t perceive, but electricity by itself, outside of a body, is also not something sentient.

This materialistic account of soul is, for Epicurus, the basis of his knowledge of death. Death is simply a loss of soul atoms, a separation of soul and body.

But neither soul nor body can perceive on its own, so this explanation of death makes Epicurus confident it is nothing to fear. We don’t need to fear that after death will come a bad experience, because it is impossible to experience anything after death. Soul and body have been separated, and the soul atoms have dispersed; there is no longer anything capable of perceiving or experiencing. After my death, I don’t exist anymore, so I definitely won’t be suffering. (It is important to note that Epicurus is only speaking to an experience of death, not that of dying. If you have always been terrified of being mauled to death by a pack of feral golden retrievers, then Epicurus, unfortunately, cannot rule out that possible future.)

Death, then, can’t be bad, and Epicurus argues that this realization should revolutionize our lives now. This is because, as Hamlet illustrates, the fear of death affects the way we live. Death is one of the things we fear the most, so removing this fear improves our lives significantly.

Accustom thyself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience; therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding to life an [unlimited] time, but by taking away the yearning after immortality. For life has no terrors for him who has thoroughly apprehended that there are no terrors for him in ceasing to live. Foolish, therefore, is the man who says that he fears death, not because it will pain when it comes, but because it pains in the prospect. Whatsoever causes no annoyance when it is present, causes only a groundless pain in the expectation. Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer.

Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus (D.L. 10.124-125)

Since death is nothing when it comes, we have no reason to fear it beforehand. This frees us to achieve the goal of life: pleasure. Epicurus defines pleasure as “the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul” (Letter to Menoeceus, [D.L. 10.131]). One of the primary troublers of our soul is the fear of death, so if Epicurus has succeeded in freeing us from this fear, our lives will be ones of tranquility and pleasure instead.

And many people would say that Epicurus has successfully freed us to live better lives. As I noted earlier, his position is still very popular. It is based in science, rather than religion—a feature attractive to many in the 21st century—and it offers peace now, rather than an abstract, intangible afterlife.

However, before becoming an Epicurean it is important to consider what objections can be put forward against this account of death. In my view the objections reveal its deep problems. I will present two here briefly, then focus on a third, one that strikes at the center of Epicurus’s account.

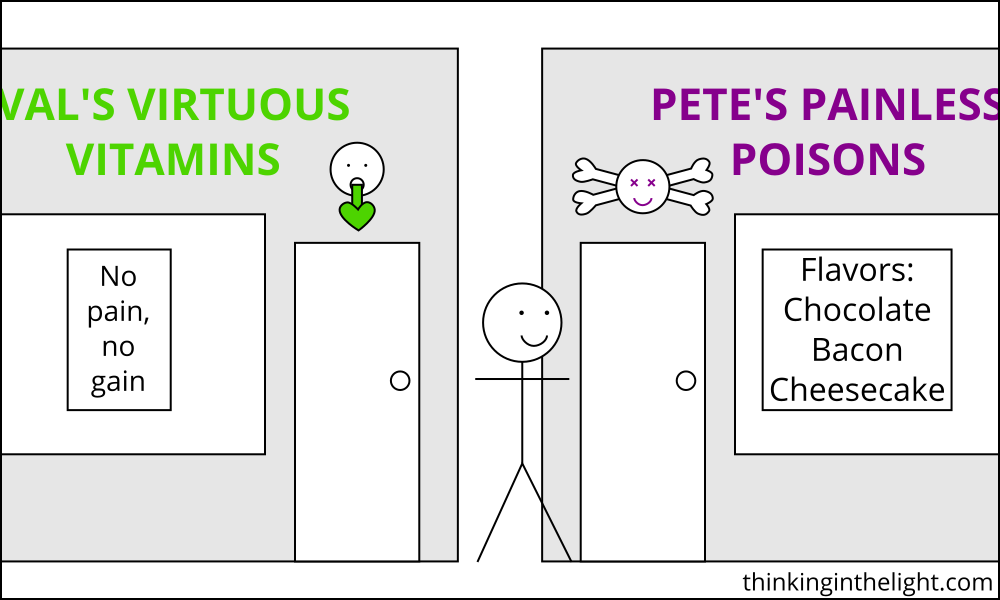

First, there is the concern that, as Hamlet is considering, suicide will be the solution to everything. The goal of life, as stated by Epicurus, is pleasure, which he defines as a lack of pain, both mentally and physically. If life brings a lot of pain—and it does—while death is an absence of pain, then it seems like death is not only the cessation of life, but also its goal. The best life would be the one that isn’t.

Now, Epicurus would likely respond that many lives are quite pleasant and there is no need to exit them. Fair enough. Even with this in mind, however, it still seems that death is as good of an option as working for a life of tranquility. And when two options are equally good, it makes sense to choose the one that is easier to obtain. In this case, dying is pretty easy, while living well—remaining healthy, avoiding stress—takes effort. So there may not be a need to escape some lives, but if Epicurus is right, there still isn’t a much of a reason to stay.

Let’s suppose, though, that Epicurus can give an adequate reason to live, one that has not occurred to me. There is a second objection to consider, one that concerns what he claims to know. Remember that Hamlet’s fear of death arises from his uncertainty, while Epicurus combats this fear through a claim to know exactly what death is like. Epicurus is very confident in this assertion, but one can ask whether he has sufficient justification for such a claim.

Epicurus grounds his position in his practice of empirical science, in the fact that his claims are based on observation. He’s right that this kind of scientific observation is crucial for many aspects of knowledge. For example, if you never look at a plant or an animal, you will not be able to say much about biology. At the same time, however, the science of Epicurus is clearly not an infallible guide to all knowledge. After all, no one nowadays would endorse his view of soul atoms. And more generally, we should ask whether observing material things is a good way to know anything about things that are immaterial. If my method limits me to things I can see, is it able to declare there is nothing I can’t? We must ask, therefore, whether we should share Epicurus’s confidence in his claims, both that of materialism generally and of a material soul specifically. Rather than demonstrated certainties, they are really closer to assertions or assumptions. He insists there is nothing after death, but this claim lies somewhere between overconfident and dogmatic.

But still he might be right. Perhaps he lucked into the correct position, or perhaps one can argue that empirical science can, in fact, demonstrate there is no eternal soul. Nevertheless, the most serious objection remains when it comes to Epicurus’s account of death, one that strikes to its heart. Even if he is correct about what death is like, his picture does not bring the comfort he seeks. The goal of his science is to rid us of fear, and he does this by explaining that death is an unconscious nothingness that, therefore, cannot be a bad experience. But aren’t there more worries about death besides the concern that it might be painful?

It is true that we don’t like pain. There are, however, other things besides pain that are bad. In the case of death, the most relevant bad thing is nonexistence.

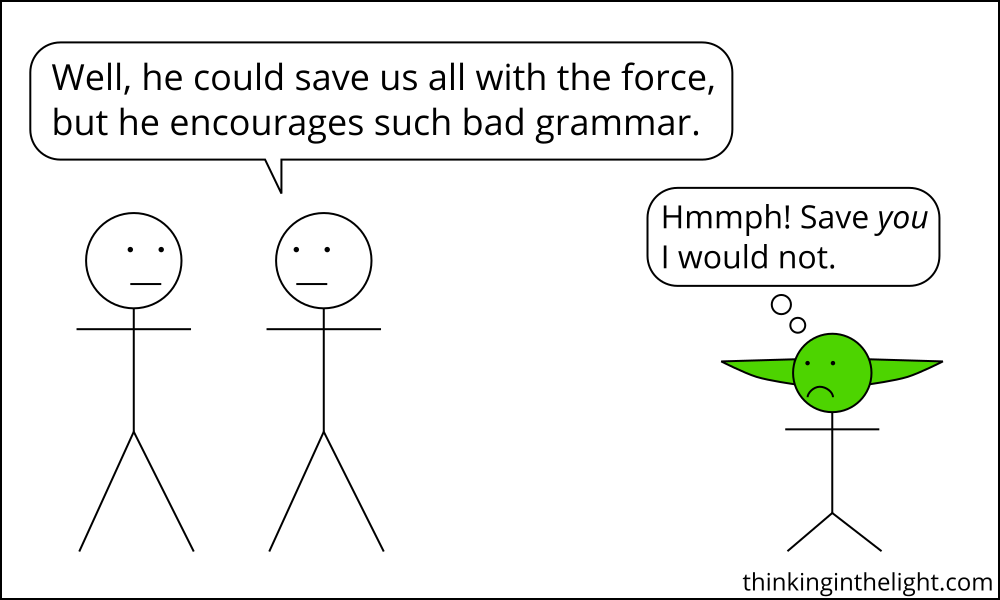

I don’t mean to say that nonexistence is always bad. It is actually good that Sauron, Thanos, and Emperor Palpatine don’t exist. And even when it comes to things that would be good, the question is not a straightforward one to answer. Is the world worse because there is no real Yoda or Gandalf in it?

For the sake of brevity, then, when I say here that nonexistence is bad, I mean that it is bad for living people to stop existing—for those who have actually existed to cease to be.

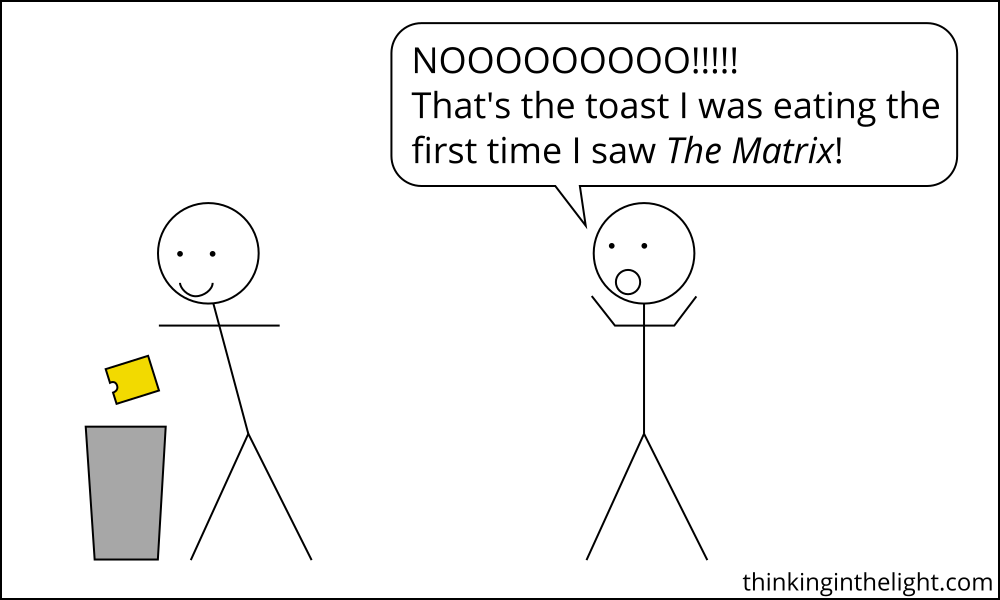

To be concrete, it is bad that my dad is not here. It is bad for us who remain, and if my dad no longer exists, it is bad for him as well. All this badness results from the fact that my dad, as a person, has value.

We regularly recognize that a human being has value simply by virtue of existing. This is why we must respect all humans, not just the ones we like. Perhaps this value comes from humanity-wide traits, like rationality, or perhaps it comes from individual traits that make each person unique. Maybe it is due to being a creation of God, made in his image. Whatever it is, we know this value exists, and we feel it. I know, and I feel as deeply as I have felt anything, that my dad was a person worth knowing. I could try to list reasons for why this is the case, but it is easier to appeal to your own experience. You, too, know people whose value is felt deeply simply in interacting with them.

And if something has value, it is bad when it ceases to exist. For example, think about the difference in your reaction if you accidentally drop a napkin into a fire versus dropping a hundred-dollar bill. Or if a tornado plows through an abandoned shack versus traveling through your house. Now, in these cases it could be that I am misjudging value, and it is not actually bad for the thing not to exist—maybe money is only worth so much to me because I am too materialistic. But as long as I think that the money has value, I will think that its vanishing is bad. The general principle holds.

This means that another statement is true by logical inference: if it is not bad for something to stop existing, then it has no value. Epicurus says it is not bad for me or for another person to cease to exist, because it is not a painful state to be in. But if it is true that our nonexistence is not bad, then this means we have no value. And we know and feel this outcome to be absurd.

So, if people have inherent value—my dad, the people you know, you, I—then it is bad for each of us to cease to exist. It is bad for the people who continue living, because they no longer experience the value of the person who has died. But it is also bad for the person themselves, because their life is worth living, their very existence is valuable. I can look ahead at my own future oblivion, and despite the fact that I will not be around to experience it, I can know that it is bad.

To reiterate, Epicurus puts everything in terms of pain and pleasure, but there are other kinds of bad than pain. A person moving from life to nonexistence is bad, for themselves and for others. And if death is bad in these ways, it is appropriate that it would affect our emotional states now, before it has reached us. If death is nonexistence, it is appropriate to fear it.

Epicurus wants to assure us that we can have a good life, one without the fear of death. We shouldn’t fear it, because we won’t exist and so we can’t feel pain. But if Epicurus is right about death simply being nonexistence, he is wrong about how we should react to this. Ultimately, for his advice to succeed—for us to feel better about death—we must pretend that death isn’t something bad.

But in the face of actual death this is hard to do. My dad’s death, if it means his forever nonexistence, is something unquestionably bad. I have no interest in pretending otherwise. I hope that this position arises out of my commitment to truth, although I must admit it also comes from my commitment to my dad.

So in my view Epicureanism is completely inadequate when it comes to thinking about death. Epicurus is not the only philosopher to downplay the badness of death, however, and in the next post I will look at another, even more explicit attempt to convince us of this. Maybe it isn’t surprising to say I will not end up being convinced. In any case, I will be in good company, since Hamlet won’t be convinced, either.

Share this post or sign up for future posts:

Bibliography:

- Epicurus. Letter to Herodotus and Letter to Menoeceus. In Diogenes Laertius: Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Vol. 2, Books VI-X). Translated by R. D. Hicks. Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library, 1925 (revised 1931). (Not many of Epicurus’s writings have survived down to our time, and the most significant ones are three letters by Epicurus preserved in this work by Diogenes Laertius.)

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. [c. 1601.] Digitized edition from Project Gutenberg: www.gutenberg.org/files/1524/1524-h/1524-h.htm