Part 5 of the series I just want what I want! (Thinking about Desires)

Noddings and the Ideal Self

Zach wants it. He wants it so bad. And it is just sitting there, unappreciated behind glass. All it would take is a snip of a camera wire, a hammer, a well-planned get-away—and the autographed, first-edition copy of Hop on Pop is his.

BOOK

LOOK

Zach wants to look into the book.

TOOK

CROOK

If he took the book, he’d be a crook.

But Zach wants it so much! Why should he turn away from his desires and instead follow morality? What motivates someone to be moral rather than do what they want?

One answer is to say that morality should be separated from desires and find a way to motivate morality without appealing to them. But another approach is to say that the problem is not with all desires, just certain problematic ones. Yes, a desire to steal usually needs to be fought against, as do desires to kill or harm. A desire to help others, on the other hand, should be encouraged. In this case we can use these good desires to motivate us to act morally. Our desire for good things can be the reason we turn away from those desires that are problematic.

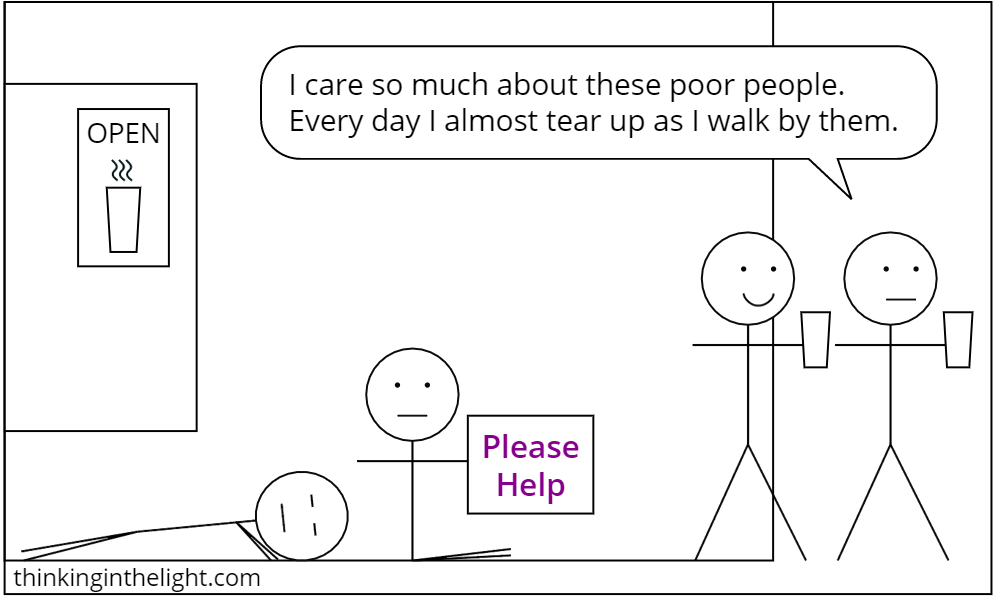

Nel Noddings puts forward a version of this second answer in her book Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. As the title of the book suggests, the good desire she wants to cultivate is the desire to be in caring relationships, and her approach is called the ethics of care. “Caring” has many connotations, though, and it is important that the caring Noddings has in view is not simply thinking nice thoughts about someone. It is actively engaging with them and aiding them when appropriate. We are to care for people, not just care about them.

In her ethics, Noddings focuses on the same question I am asking here: What motivates us to be moral? We can put this in terms of caring: Why would I care for someone when I don’t want to? Take Allie and her brother, Nate. Nate has made a lot of bad choices in his life, so he is needy and unpleasant to be around. When Nate is in difficult circumstances, he turns to Allie because she is his sister. If she did what she wanted, she would just ignore him and go on with her own life. What would motivate her to turn her attention to Nate and help him instead?

Noddings rejects a few answers to this question. For instance, our motivation is not based in abstract principles, such as those provided by utilitarianism or by Kant. Zach doesn’t motivate himself by saying “stealing is always wrong,” and Allie doesn’t motivate herself to care for her brother by telling herself that siblings simply have an obligation to help each other. Noddings also rejects appeals to ideals lying outside ourselves, such as God or universal love. Instead, she wants to keep things grounded in the details of our daily lives. Allie is going to motivate herself by immersing herself into her life, not by pulling back from it and turning to God.

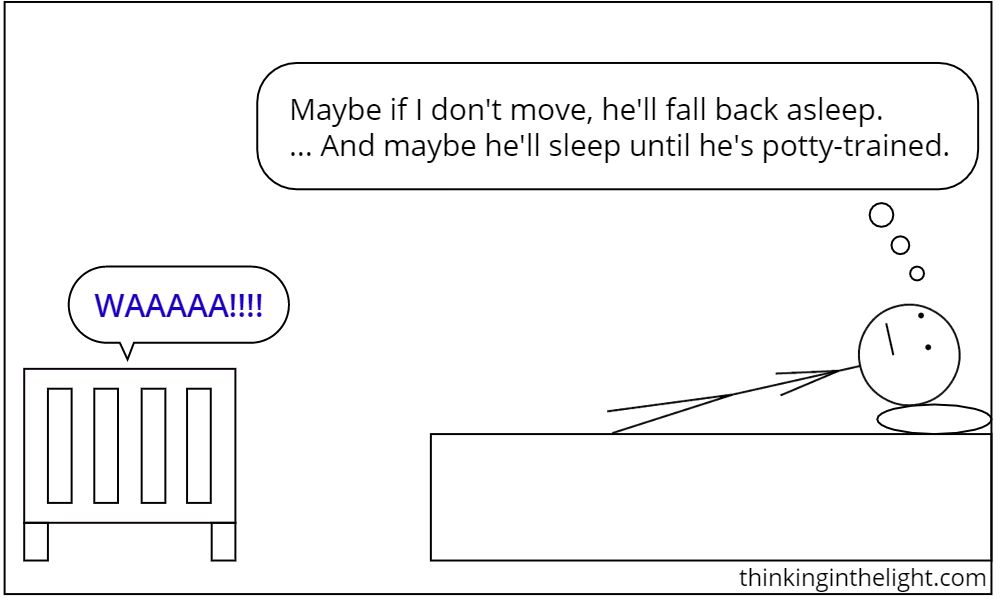

Given this emphasis on the concrete particulars of life, Noddings starts from the fact that there are times when we just do care. When Allie enters her apartment and sees her roommate on the floor crying in pain because she just broke her foot, Allie is likely to be totally absorbed in the plight of the roommate. Allie is not resenting her need, but she simply wants to help her. She feels that she must care, in the sense that she is overwhelmed by a desire to help. To illustrate this feeling, Noddings likes to use the example of a mother caring for her infant. When the infant cries, the mother feels an overwhelming need to pick up the child and comfort it. (Full disclosure: I have never been a mother, so I’m relying on reports that this feeling towards infants takes place. As a father, I must admit my reaction to crying infants was different.)

This feeling of wanting to care is central to Noddings’ ethics, but on its own it is not necessarily an example of ethical behavior. It is just something that happens. For example, animal mothers exhibit this behavior as well. This state of automatic care for others is the one we want to reach under an ethic of care, but it is the wanting to reach it that is the ethical part.

I want to reach this state because as I think over my life I remember the times I acted in care and the times I was cared for. In the remembrance, I feel that this caring is good. In particular, when I think about myself in caring relationships, I recognize this as my ideal self. I am at my best when caring. In the midst of this remembering and recognition, if I am presented with an opportunity to care for someone, I again feel that I must care. This second ‘must’ is different from the first, however. When Allie felt she must care for her roommate, it was the must of overwhelming desire. But this second feeling is the must of ethical obligation. I must care because I ought to, even if I don’t want to right now.

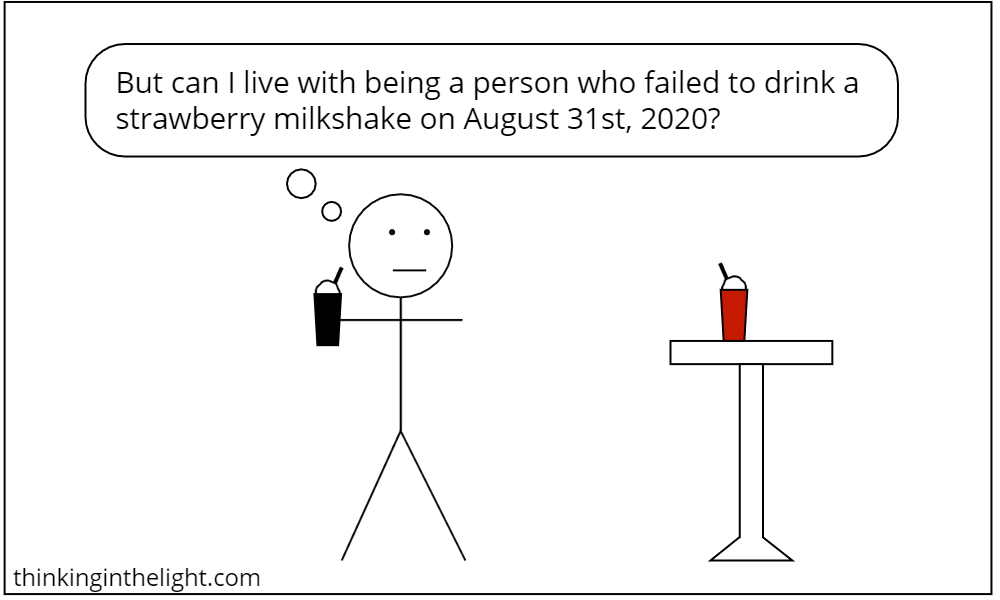

So, when I encounter a situation where my desire is to not care for a person, this second feeling motivates me to care anyway. There is a conflict between two of my desires: “I don’t want to help this person in this situation” vs. “I want to be my ideal self, which is a caring person.” This choice is not like one between the competing desires for having a chocolate milkshake or having a strawberry milkshake. In that case the two desires are of the same sort, and while I (sadly) can’t have both satisfied, it really doesn’t matter which I choose.

It does matter when my ideal is involved, however. When I choose not to care for someone and act against my desire to be my ideal self, I’m ripping myself in two. I am consciously violating my ideal. On the other hand, I could build up my ideal instead, if I go against my temporary, situational desire not to help in this case. This ideal motivates me to care, makes me feel I ought to care, because it is only by acting in accord with it that I can be the person I want to be.

Am I, then, suggesting that the answer to the question, “Why should I behave morally?” is “Because I am or want to be a moral person”? Roughly, this is the answer and can be the only one…

Caring, p. 50

When Allie is presented with her brother’s need and her own desire to avoid him, she is faced with a choice. Is she going to act on her desire for comfort or will she forgo comfort and act on her desire to be a caring person? She cannot be a caring person if she fails to care for this concrete person in front of her who has both ties to her and a felt need. So she puts aside her desire to avoid her brother’s messy life and cares for him. This doesn’t mean that she will do whatever he wants or that there are not situations she needs to leave for her own sake, in order to remain a caring person. But she does prioritize her desire to be a caring person over her desire to remain uninvolved.

And when she acts on this feeling that she ought to care, she might even start to engage with her brother in such a way that she shifts to the first sort of feeling. As she enters into his situation, she has the opportunity to feel not only that she wants to be a caring person, but that she wants to help this individual whom she previously did not. This is the ultimate goal, where she is caring for someone directly and hence living out her ideal.

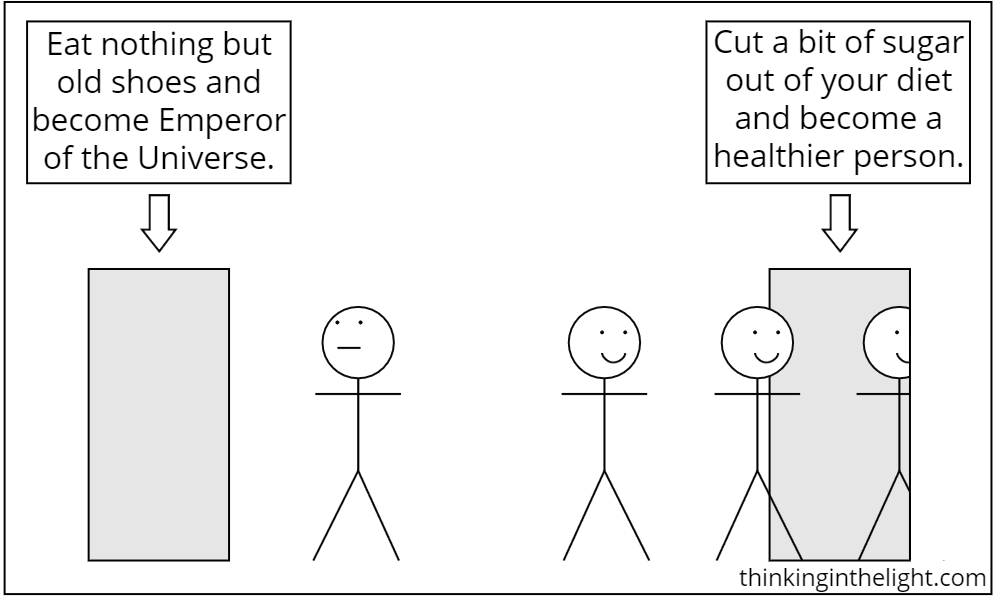

Note that Noddings’ ideal self is different from an abstract ideal passed down by God or reason. It arises out of reflection on my own lived experience. As such, it is concrete and attainable, something I can put into practice in real life. It is an ideal I give myself, not something handed to me from elsewhere. It is this last part that is important for my purposes in this post. We are motivated to act morally, because our ethical ideal is something we ourselves desire. This desire for an attainable ideal, then, can overrule our desires in individual situations.

This is quite an attractive picture. Noddings’ vision of the ideal self is admirable, and it fits with what a lot of people would see as a good person. Whatever else we think about morality, caring is certainly a large part of it. This account of the ideal self is also a reasonable explanation for why I would be motivated to forsake my selfish desires. It is definitely easier to follow and more intuitive than the account given by Kant.

Nevertheless, there is a problem with Noddings’ account. The key desire that overrules my others is the desire to be my ideal self. But my conception of my ideal self is just that—my conception. For Noddings, my ideal self is rooted in my feelings. She is relying on the fact that I feel my ideal self to be me in caring relationships, that I feel caring to be good and me caring to be me at my best. But what if I don’t feel this way?

Take Mark. When Mark thinks back over his life, the times he has felt the worst are those when he has felt overwhelmed and out of control. By contrast, the best times have been those when he has had the power to control his circumstances and other people. He feels that he is at his best when he is powerful. His ideal self is exercising power.

Now, it could be that the Marks of the world are only a small subset of people, but clearly they exist. And it is quite likely that there is a larger set of people (maybe even the majority?) whose felt ideal would be a balance between caring and power. Their ideal is to care for and receive care from an in-group, while exercising power over the out-groups.

People who don’t feel caring to be their ideal are a problem for Noddings. She sometimes says that seeing caring as good is inevitable or universal, but she also acknowledges that darker impulses lie within us as well.

I am not denying the reality of this dark side of feminine character, but I am rejecting it in my quest for the ethical. I am not, after all, suggesting a will to power but rather a commitment to care as the guide to an ethical ideal.

Caring, p. 42

It is fine for her to choose this ideal if she feels it is her ideal, but, unfortunately, she has no basis for arguing with another who feels differently. Since she appeals to feeling and the two people feel differently, there is nothing she can appeal to. She clearly thinks her felt ideal is the correct one, however, which means that those who have different feelings must simply be marginalized.

One either feels a sort of pain in response to the pain of others, or one does not feel it. … For one who feels nothing, directly or by remembrance, we must prescribe reeducation or exile.

Caring, p. 92

Now, at least part of what she has in mind here are psychopaths—those who truly feel nothing at causing pain to others. But Noddings would ultimately have to say the same thing about someone whose overriding feeling is a need to exert power rather than a need to care. When it comes to ethics, there is nothing outside of our desires and commitments, nothing outside of how we feel. Even rights are based on these.

There are, strictly speaking, no natural rights—only rights we confer upon each other out of natural inclination and commitment.

Caring, p. 120

And if all of ethics depends on how we feel, we are at an impasse when we feel differently.

Striving to be my ideal self sounds noble. But if I am the origin of this ideal, then ethics is fundamentally about myself. Acting on what I feel my best self to be is simply satisfying my greatest desire. If this desire is faulty in some way, if my ideal is misshapen, then how is my action any better than that of the person who is casually selfish? If Mark exercises much self-control and does many things to help others, but this is all in pursuit of his ideal of becoming powerful and wielding his influence over others, this is no better than the man who simply gives in to his immediate desires to place himself over others.

The problem is that in Noddings’ ethics there is nothing to call us outside of ourselves if we need to be so called. I can pit one part of me against another all day long, but in so doing I will never leave the confines of myself. If there is anything faulty about me at my core, something that warps my desires and taints my feelings, then my self-produced ideals will always fall short. I will never achieve goodness by following them. Ethics requires a source of morality that lies outside myself.

For example, this role—being a source of morality—is one often attributed to God. Noddings is clear that God is not needed in her picture, that human relationships are an adequate foundation for ethics. She goes further and regularly criticizes the Christian view of God, particularly the story of Abraham, who is asked to abandon his natural care for his son and sacrifice him to God instead. Noddings tells a story of a woman who leaves religion due to its faults and seeks ethics in the concrete details of life:

For many women, motherhood is the single greatest source of strength for the maintenance of the ethical ideal. The young woman who has just given birth to a child may, if she has a religious faith, turn in wonder and gratitude toward the God she thanks for the safe delivery of her child. But she may equally well lie awake all night thinking on this strange God. Already she feels the likelihood of eternal love and tenderness toward her child; she cannot imagine visiting long or cruel punishment on him. What, then, of God or gods? Why, she wonders, would an all-knowing and all-good God create a world in which his creatures must eat each other to survive? Why, oh why, would he withhold his physical presence from them? Why would he demand that they—much the needier and weaker—love Him? When he-who-has-not-lost-his-faith answers her by saying, “We must not question,” she turns, finally, reluctantly, decisively away. This, also, she would not say to her child: You must not question.

Thus she turns to this earth and to these concrete others for her strength.

Caring, p. 130-131

Now, I agree that there is a problem with the religion in this story. Telling someone not to ask questions is never a good answer. When I see Christians do this it irritates me incredibly. If God made our minds, we ought to expect that he means us to use them.

It is also the case that Noddings has an inadequate view of Christianity. Nowhere in this story is there even a hint of why the Bible would declare that God is love (1 John 4:16). The central piece of the Christian story is a God who loves humanity so much he solves their biggest problem for them—their apathy towards their good creator—and he does this despite their apathy. Not to mention that this involved coming into the world physically and includes a promise of dwelling with God forever.

But more fundamentally, if God exists, he might call us to do something that goes against our impulse to care—to be related to another person—and in this case “caring” would be wrong. If God knows everything, as he would if he made it all, and if I don’t know everything, which might possibly be the case, then just because he asks me to do something that does not appear caring to me, this does not mean it is not good. Quite the reverse. If I knew that someone was both omniscient and benevolent, wouldn’t this be the person whose judgment I would always defer to?

Caring is clearly a large part of ethics, which is why Noddings is so compelling. But caring is not everything, especially when this means what I feel to be caring. In the next post I will wrap up this series on desires by going back over a few of the topics it has touched, as well as exploring further God’s role in the tension between our desires and morality.

Bibliography:

- Nel Noddings. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. [1984. Original subtitle: A Feminine Approach…] Second edition, Updated. University of California Press, 2013. (Noddings is not too difficult to read, since she was writing in the 1980s. The core of her ethical theory comes in chapter 4, “An Ethic of Caring,” although there are scattered bits throughout the book that supplement what she says in it. As I note here, the original subtitle was not “A Relational Approach,” but “A Feminine Approach.” Throughout the book Noddings proposes that the history of ethical thought went the way it did because it was written by men, and she sees her position as embodying a woman’s perspective by contrast. In the post I have sidestepped this issue, since in my view it can be separated from the content of her ethical theory.)